Part of living in a functioning democracy is the mass availability of information to the general public, allowing us to interpret and make sense of the world around us. Whether we’re reading newspapers, watching news channels or perusing magazines, we’re exposed to a vast array of stories as we go about our daily lives. Ultimately the media we’re exposed to affects and shapes our sense of reality, having implications upon what we judge to be moral and truthful.

Although we may perceive what they’re being exposed to be the truth, media is subject to conditions that directly impact how a story or event is reported, interpreted and depicted. So as we read our newspapers on the way to work or flick through our favourite magazines, how certain can we be in knowing that what we’re exposed to is factually truthful?

The propaganda

One way of understanding the nature of the media environment is through the Propaganda Model. Developed by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, the propaganda model is a means of scrutinising the hierarchical structures and forces inside the mass media industry responsible for how a piece is crafted and presented.

“While it is true that the PM does not ‘test’ effects directly, ‘it is important to note that this was not Herman and Chomsky’s intention in the first place.’28 In fact, as highlighted earlier, ‘they deliberately state that their PM is one that deals with patterns of media behaviour and performance, and not effects.”

Jeffery Klaehn: A Critical Review and Assessment of Herman and Chomsky’s`Propaganda Model’

The model identifies 5 forces, or filters, that have the potential to cause the mass media to play a propaganda role. And, although it is easy to interpret it as such, the propaganda model is not one that’s meant to suggest a conspiracy. The label of conspiracy theory is one Noam Chomsky vehemently rejects.

Chomsky argues that “the PM actually constitutes a ‘free market analysis’ of media, ‘with the results largely an outcome of the working of market forces’.” These influential forces are Ownership, Advertising, Source, Flak, and Agenda. Besides, the forces highlighted aren’t hidden and can be easily observed by the public.

The model merely encourages us to ponder the implications and effects media has on our understanding and thought processes concerning the world around us.

Ownership

When considering how media ownership affects the media landscape we must account for the role and influence wealthy elite entities exercise. Whether online or print, Media barons and conglomerates hold sway over the media landscape.

Factors such as a news organisation’s size, individual shareholdings, capital and profit orientations can determine a piece’s slant or angle. As noted by Christian Fuchs in ‘The propaganda model today’, “wealth and power inequalities shape what is considered newsworthy, what gets reported, and what is heard, read and watched.”

Using the wealth that they hold, these elite entities can still further their dominance over the media landscape. They may acquire rivals to increase their market share and exploit the prohibitive costs involved with meaningful competition. This can have a detrimental impact on public discourse, if not appropriately managed. Audiences may find themselves in an enclosed media system that determines and narrows the scope of what topics, issues and events are deemed newsworthy.

Advertising

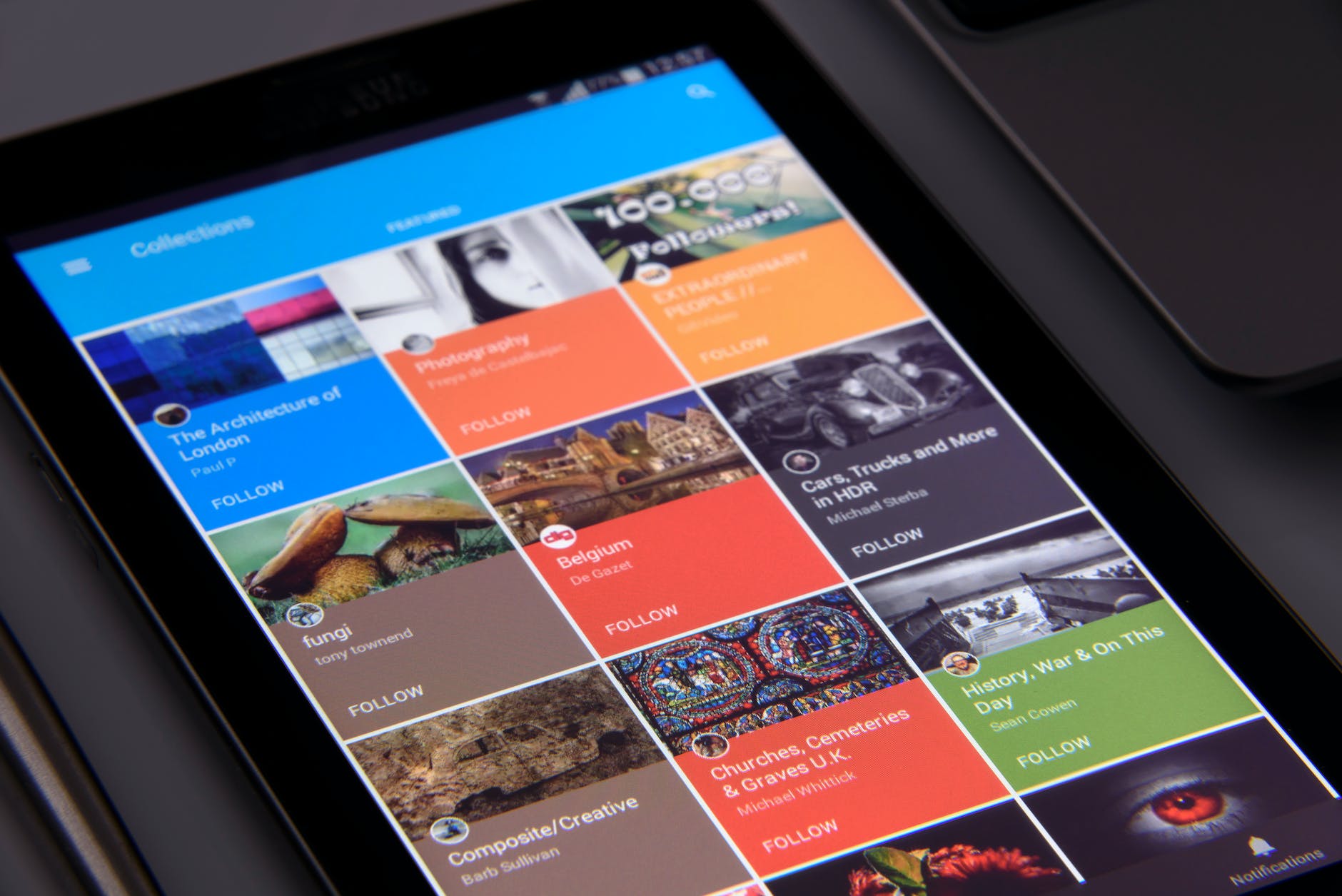

Like any functioning business, media outlets rely on revenue generation. Some publications and online media sites may charge one-off payment or a subscription fee whilst others provide free access. In any case, the primary form of funding for mass media publishers and outlets is Advertising.

Mass media seeks to make their publications as attractive and advertiser-friendly as possible. They provide ad-placement opportunities to reach their ideal target audiences, raising awareness of brands, products and services. So with mass media generally being for-profit and supported by for-profit entities, outlets are careful to ensure their publications or online platforms offer an accommodating environment.

Advertisers not only want their ads to be seen, they want their ads showcased on platforms aligning with corporate social responsibility (CSR) values too. Ultimately, the need for advertising revenue affects editorial decisions affecting the framing of stories, events and topics before publication.

Source

Journalists and media outlets are constantly on the lookout for newsworthy stories to publish. However acquiring stories first-hand is often a time-consuming process that puts pressure on journalists working in mass media, where publications often require a fast consistent flow of content. As such, journalists may form a symbiotic relationship with ‘source providers ‘ such as PR practitioners.

Public Relations “plays the central role in the design and implementation of information subsidy efforts by major policy actors’ and about this subsidy, he says that ‘the source and source’s self-interest is skilfully hidden”.

Gandy, 1982, cited in: ‘Rethinking Public Relations: PR Propaganda and Democracy’

However, in maintaining such relationships, it can be assumed that media conveyors, like journalists, produce stories in tandem with the aims of source providers. But, other voices disagree with this assumption. In ‘The Herman-Chomsky Propaganda Model: A Critical Approach to Analysing Mass Media Behaviour’, Mullen and Klaehn express that “such relations frequently become adversarial when interests diverged.”

This suggests a loose relationship between source providers and media conveyors. As such, coverage benefiting source providers isn’t guaranteed. Consequently, the factual integrity of coverage is subject to the accuracy of witness or authoritative expert statements, journalistic interpretation, and the editorial slant of media outlets.

Flak

Flak, as a filter, serves as a means of disciplining the media. According to Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, flak is a mechanism: “to provide “experts” to confirm the official slant on the news, and to fix the basic principles and ideologies that are taken for granted by media personnel and the elite, but are often resisted by the general population.”

Therefore, flak brings mass media coverage back into the domain of what’s considered to be acceptable talking points or facts concerning an event or story. Pressure, or flak, on mass media outlets, can derive from their audience, Ofcom complaints, petitions, and fact-checkers to the criticism of social media users.

Ideology

Initially labelled ‘Anti-communism’, the 5th filter in the propaganda model is Ideology. In a modern context, a broad spectrum of ideologies exists in the mass media landscape, driving rhetoric and the positions mass media outlets adopt when conveying information about topics and issues within society. So, as well as anti-communist rhetorics, you may have encountered anti-racist, anti-immigration, classist, feminist, and LGBTQ stances, as well as many others.

This filter can create a form of tribalism among audiences on societal issues that unite or split regional, national and international communities. To an extent, ideological tribalism is enforced by flak, with audiences pushing back against publications that adopt positions contrary to their own. And if audiences walk away or boycott, this reduces advertiser confidence and willingness to buy ad space. This means for-profit mass media outlets may entrench themselves on ideological positions regardless of whether their slant is truthful or factually correct.

Leave a comment